Falling into inquiry

Many who are new to international teaching find themselves expected to deliver and/or construct an inquiry-led curriculum in English despite limited training to do so. What are the considerations that come with such a switch?

The current state of inquiry

Let’s start with acknowledging that inquiry has a bad name with some. In the worst case it may conjure images of a feckless teacher asking kids to ‘get their laptops out’ and do some ‘inquiry’ as they walk around nodding speciously, the words 21ST CENTURY LEARNING reverberating around their head.

Such aimless, but in many cases well-meaning methodology, undoubtedly leads to cognitive overload for students in the cases where they are actually trying to learn and not playing on Minecraft.

For me, inquiry is not allowing the kids to figure out the core factual and procedural knowledge of English themselves. This would be a colossal waste of time and is best done in a ‘direct instruction’ approach with all the appropriate modeling, chunking, sequencing, non-examples and the like.

Where inquiry plays a part is to harness students’ experiences, passions, personal opinions and prior knowledge to give individuality, flair and enthusiasm to a unit of study. Building in opportunities for inquiry done through media, interviews, surveys or observation can give students a greater sense of ownership and connection to an outcome that they are still demonstrating curricula knowledge and skills in.

This comes at a cost, however. Inquiry can be a time consuming process given the need to model appropriate practices, allow adequate time for research and reflection, check in with respective students and deal with unique challenges as they arise. There is necessarily a need to limit the amount of factual or procedural knowledge that can be taught as a result of this.

At this point, I can see why some may turn their back on an approach that intentionally leaves disciplinary concepts and threshold ideas until later in the course, therefore stymying the overall scope of the taught curriculum.

But regardless of the polemic that often defines these inquiry v direct instruction discussions, leading practitioners of inquiry would agree that some front-loading is always necessary. Trevor MacKenzie refers to the need for non-negotiable content in his book as well as in an interview I did with him here. He also makes explicit mention of state standards needing to be met in teachers’ respective countries of origin, therefore limiting the amount of inquiry that can be done.

The IB also references front-loading at multiple points in their MYP literature, acknowledging that facts play an important role in inquiry-led learning sequences:

“The goal of teaching and learning in the MYP is the active construction of meaning in which students build connections between their prior understanding and new information and experience that they gain through inquiry. “Front-loading” content (efficiently building background knowledge) can be important, introducing a base from which to teach skills or practise critical thinking. Effective inquiry often is not possible without facts and prior knowledge.”

What, When, Where and How?

Despite the bridge building between two approaches that are sometimes portrayed as absolute ends of the spectrum, I have often struggled with a series of questions regarding inquiry:

What should inquiry actually consist of?

When should it be done in a sequence of lessons?

Where should students be expected to conduct the inquiry?

and

How much time should be devoted to it?

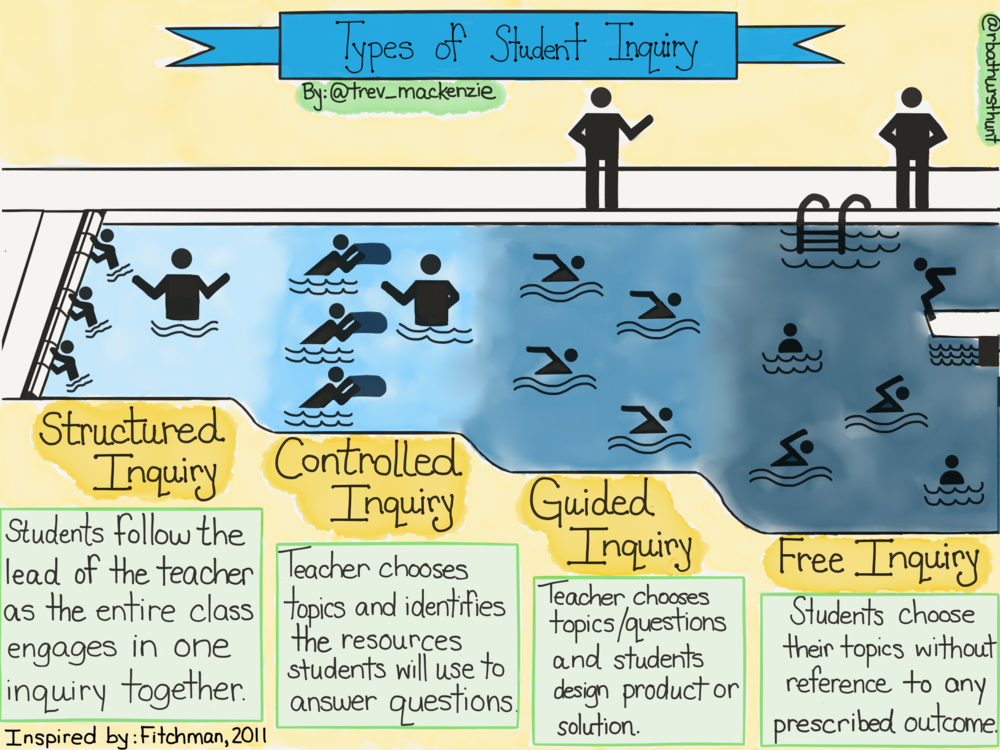

McKenzie does a good job of outlining some of what inquiry might involve and a decent stratification of the way it can be scaffolded as shown below:

Courtesy of Trevor MacKenzie

Necessarily, I would offer that the deeper you go in the pool, the more time needs to be given over for inquiry and less time devoted to explicit teaching of core curriculum content.

And yet I’m not fully satisfied.

In a mood reminiscent of Adam Boxer further probing the already excellent framework of Barak Rosenshine, I find myself asking: but how long do I give for X in this inquiry process and when do I tell them to Y?

In order to give emerging teachers as well as established colleagues the best advice on how to knit inquiry into the curriculum, we need to be able to have robust subject conversations about the technicalities of its inclusion. Currently, I’m not sure a framework exists that can guide the way on this.

A secondary consideration is the relative role of inquiry in relation to students’ age. It seems to me that in a 3 or 5 year MYP course, a curriculum would build towards the upper years being heavier in terms of student autonomy, having built the necessary foundations in middle school. Add to this the maturity, impulse control and social skills that develop over the course of high school, it seems logical to expect a process that hands over autonomy to students to operate on a sliding scale geared towards independence in the upper years.

And yet, Mckenzie states that each year level he teaches follows the tiered approach espoused in his book and outlined above. Meaning that Y7 are spending a quarter of their academic year working on an assignment that employs ‘free inquiry’.

My reservations about this may be heavily influenced by the MYP framework and the expectation that every assessment strand be assessed at least twice a year. Meaning that the likes of ‘non-verbal communication’ not only be assessed twice but be assessed a second time under circumstances where students have had to take greater autonomy over their learning of such a skill.

MYP Inconsistency

There have clearly been attempts to allow for inquiry based learning at the heart of every MYP unit. Assessment strands and descriptors reveal the liberty that departments, teachers and students may potentially have, given the descriptors’ relative lack of specificity. An example can be found under Criterion B iii: use referencing and formatting tools to create a presentation style suitable to the context and intention.

Such a criteria allows a unit’s outcome to range from an essay in which the student would use paragraphing and MLA9 to a YouTube video that makes use of certain transitions and offers links to research in the show notes.

Yet for all the independence this engenders, I return to the obligation departments face in which data is expected for every strand like this, twice a year. Immediately, this forces teachers into deciding where each of the 15 strands will be taught towards, combined into respective units and ultimately assessed. Given the additional expectation that assessments be ‘authentic’ and not a multiple-choice quiz for example, there is a need to ensure that strands are brought together from across the curriculum in an organic manner that befits the subject.

Asking ‘inquiry’ to be at the heart of such a curriculum presents a logistical quandary. To what extent and how much are students expected to discover the relevant skills or knowledge on their own? Should this be the same in every year level? Testing them twice a year requires that schools dedicate roughly 14 weeks to ensuring that every strand has been taught towards or exposed to students in some way. Can teachers realistically setup Year 7 in the first half of the year in order to take greater autonomy in the second half?

Muddying the waters further

English teachers have had the benefit of at least 5 seminal books in the past decade or so:

Reading Reconsidered by Doug Lemov, Colleen Driggs and Erica Woolway

Robust Comprehension Instruction with Questioning the Author by Isabel L. Beck, Margaret G. McKeown and Cheryl A. Sandora

Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction 2nd Edition by Isabel L. Beck, Margaret G. McKeown and Linda Kucan

The Writing Revolution by Judith C. Hochman and Natalie Wexler

Crafting Brilliant Sentences by Lindsay Skinner

All of which have help to cast light on the messy procedures of reading, writing and vocabulary acquisition. The common message being that teacher-led instruction, modelling and intervention is crucial all the way through school.

Speaking as someone who has tried hard to implement the lessons offered in these books, the results are compelling.

It is therefore hard to ignore the clear impact that such instruction has on students, particularly when you are leaving the state sector with hard fought experience of its success and then being asked to teach students in a way that doesn’t seem to yield the same, immediate or convincing results.

Such an expectation should be based on presenting inquiry with passion, backed with all the practical and up to date advice with regard to its implementation as a pedagogy.

The most recent findings on inquiry

The IB, wanting to review the way inquiry is being utilised in its ‘eco-sytem’, helped to publish this report, which is also summarised here by Dr Joseph L. Polman and Dr Karla Scornavacco out of the University of Colorado Boulder.

In it, the professors raise a number of interesting considerations for the IB, IB World Schools and IB teachers moving into 2023 and beyond.

Firstly, there is a direct call for the IB to improve the way new teachers are ingratiated into the inquiry method:

Teachers who are new to ITL (inquiry teaching and learning) or uncertain of how to implement this ambitious teaching model—whether they are new to the profession or veterans—need to be able to access resources and participate in activities that support their professional growth regarding ITL.

They go onto suggest the importance of book studies amongst professional communities so as to establish a shared understanding of how inquiry works in their respective institutions.

More tellingly, the paper is also calling upon the IB to give more specific guidance as to what inquiry activities actually entail within their guides:

integrate more explicit attention to ITL strategies and stipulate discipline-specific inquiry learning goals, and particular disciplinary practices that are worth stressing

And although aimed more at the Diploma Programme, I think Polman and Scornavacco’s advice regarding the DP could also be levelled at the assessment heavy nature of the MYP course:

Our findings lead us to recommend that IB publications, IBEN-sponsored events and conferences, and locally organized professional learning community activities openly address the tensions and tradeoffs of time, coverage, and external examination preparation

In summary

There is considerable amount of research that dispels the effectiveness of inquiry, when it is done without consideration for student’s cognitive load

Teachers who are new to schools, international or not, and expected to teach from an inquiry stance may already be aware of such criticism and therefore need to see significant passion, support and guidance for how to implement it in their practice effectively

The likes of new knowledge, processes and skills, such as those expertly outlined in the likes of Reading Reconsidered, may need to live alongside inquiry as a methodology

This is to ensure students have the best eventual outcomes in English as a subject and avoid alienating teachers who have had success using direct instruction in previous schools or systems

The IB has been advised to do more in terms of guiding where, when and how inquiry features in the curriculum for respective subjects

In the meantime, communities in schools are encouraged to come together and read the likes of Kath Murdoch, Lynn Erickson, Trevor McKenzie and the respective academics writing about inquiry in their discipline to find a clear sense of approach in their context