Does the MYP call for a ‘sage on the stage’ or ‘a guide on the side’?

I recently attended a CPD event in which the external speaker continually championed the guide on the side > sage on the stage advice. This was a day designed to boost teacher’s application in the MYP across my foundation.

As with most false dichotomies, the sage v guide opposition unhelpfully leaves little room for nuance.

Who or what is the sage on the stage?

My understanding of the sage on the stage is the ‘traditional’ depiction of a teacher imparting knowledge with the expectation that all students attend to it by taking notes or rote memorisation in some way. This knowledge will then be tested, whether formally or informally, before the next element of the scheme is explored, building on what has come before. It has been referred to as direct instruction or explicit instruction by some, irrespective of their teaching philosophy.

Who or what is the guide on the side?

This role, to the best of my knowledge, describes a teacher who may begin a unit of learning by posing a problem, project or introducing the final assessment before allowing students to attend to the knowledge and skills necessary through a more unstructured approach. Whether this be asking their own questions, doing research, making their own way through preprepared materials or simply reflecting on what they already know, the teacher takes up a vantage point that allows them to observe respective progress from a distance and aim to catch students before they fall into misconceptions or unhelpful behaviours. It has been referred to as inquiry, project-based or constructivist learning by some, irrespective of their teaching philosophy.

Does the MYP want a sage or a guide?

The most recently published document I used in pursuit of an answer to this question is the MYP Principles into Practice, updated for 2022.

The following is a snapshot of the text in terms of what an MYP education should consist of:

“develop inquiring, knowledgeable and caring young people who help to create a better and more peaceful world through intercultural understanding and respect.” (IB pii)

“offers students opportunities to develop their potential, to explore their own learning preferences, to take appropriate risks, and to reflect on, and develop, a strong sense of personal identity” (IB, p3)

“It was intended that this curriculum would share much of the same philosophy as the DP and would prepare students for success in that programme.” (IB, p3)

“A focus on higher-order thinking skills”. (IB, p4)

“acquire the necessary skills, knowledge and attitudes to be successful.” (IB, p7)

“feature structured inquiry, drawing from established bodies of knowledge and complex problems. In this approach, prior knowledge and experience establish the basis for new learning, and students’ own curiosity, together with careful curriculum design, provide the most effective stimulus for learning that is engaging, relevant, challenging and significant. (IB, p11)

“engages the intellect on two levels—factual and conceptual—and provides greater retention of factual knowledge because synergistic thinking requires deeper mental processing” (IB, p16)

“Front-loading” content (efficiently building background knowledge)…introducing a base from which to teach skills or practise critical thinking. Effective inquiry often is not possible without facts and prior knowledge.” (IB, p66)

Much of the above can be placed into one of two categories: knowledge / skills acquisition or holistic development as a learner.

The latter comprises of having students develop their ability to reflect, collaborate or embrace their individual identity alongside or during their studies. The former stresses the need for facts, prior knowledge and critical thinking that will prepare them for external examinations in the IBDP or CP and beyond.

So, can a ‘sage’ or a ‘guide’ fulfill both of these categories simultaneously?

Acquiring facts or ‘base’ knowledge

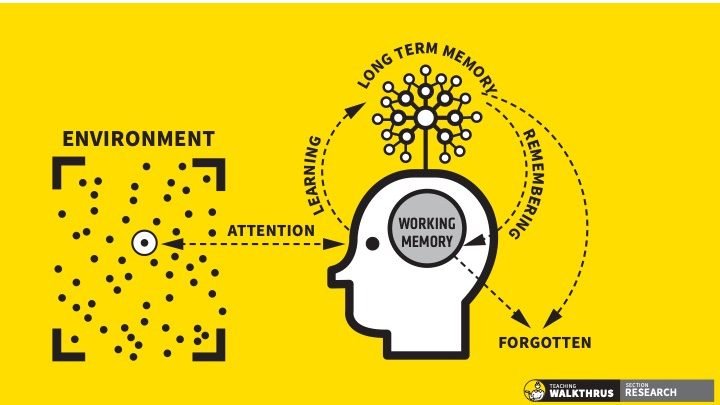

A very popular model to explain how we learn is Willingham's, depicted here by Oliver Caviglioli:

Courtesy of Walkthrus by Tom Sherrington and Oliver Caviglioli

Anything from our environment that we pay attention to enters into working memory. If we can successfully process or attend to what we are paying attention to, this leads to learning. One way to define learning is that a change is made in your long-term memory (Kirschner, Sweller and Clark, 2006). You can recall what has been learnt by remembering this knowledge and reactivating it in your working memory.

Crucially, if there is too much information entering your working memory from the environment then the knowledge or skills you are paying attention to will be forgotten once the period of attention ends. Similarly, if something remains in your long-term memory without being remembered or recalled for a significant period, it too will be forgotten.

Many have found fault with the lack of nuance in the model from a psychological standpoint but in terms of its utility for teachers, the simplicity is key in communicating the vital relationship between what is to be learnt, how it enters our memory and how it is retained or forgotten.

Taking this model and the understanding that learning is a change in long-term memory, we return to one of the MYP’s missions that is to introduce a base of knowledge on which inquiry can take place.

This ‘front-loading’ as it is described to in Principles into Practice, refers to students engaging in the three stages of cognitive processing needed to commit something to their long-term memory (Fiorella and Mayer, 2015):

Stage 1: Selecting relevant information from the material provided

Stage 2: Organising the material into a coherent structure in working memory

Stage 3: Integrating it with relevant prior knowledge activated from long-term memory

Considering these stages, it is not yet clear whether the guide or the sage is better prepared to take the students through each part.

However, Fiorella and Mayer go onto explain that successfully ‘selecting’ information is dependent on being able to discriminate between what is important from what is not in the materials provided (Fiorella and Mayer, p. 13).

Added to this is Tom Needham’s observation that organising the material in working memory, Stage 2 in Fiorella and Mayer’s research, can quickly become problematic and confusing unless it is broken down into manageable chunks and introduced at a rate that does not cause cognitive overload (Needham, 2022).

Lastly, for Stage 3 to occur and for there to be a change in long term memory, Needham also observes that “a student needs to already possess relevant prior knowledge to connect it to.” (Needham, 2022). Without this, even if sufficiently retained in long-term memory, the knowledge will remain an island of information that offers no realistic application for the often multifaceted tasks expected in secondary education.

Let’s consider the pros and cons of the sage and guide respectively in terms of implementing the above stages:

Based on these considerations, the sage is better placed to ensure the new knowledge base is successfully taken onboard. As well as this, they can make centralised preparations to ensure it is retained in the short and long term for all students in a class.

Despite this, most subjects do not rely on a framework of pure factual knowledge to achieve success. For most, these factual ideas are often intrinsically tied to the skills or processes at the heart of a subject’s domain.

In English for example, we can teach students what ‘enjambment’ is in poetry. But recalling the definition or merely spotting it in a text is insufficient when it comes to analysing its use.

Therefore, once a certain body of knowledge has been acquired, who is best suited to aid students’ appreciation of skills or processes in a subject: the sage or the guide?

Acquiring skills

Pooja Agarwal’s 2019 paper explores the idea that closed or simple retrieval practice will not adequately prepare students for more complex tasks like extended writing or problem-solving. Rather, higher-order quizzing is needed to prepare for higher-order writing.

This higher order writing is also a product of critical thinking within the subject domain. Such a skill is typical of those deemed ‘experts’ and something that is highly coveted as a goal of the MYP framework.

Despite this, the mental networks present in the mind of an expert and a novice differ greatly.

Needham’s observation is that “when solving problems or engaged in cognitive work, experts rely upon their larger and more developed long-term memory deposits, patterns of information that are also called schemas.” (Needham, 2022). These schemas or long-term memory deposits are largely absent from novice or students minds as they are yet to attend to such learning and build connections between the body of knowledge needed in the subject.

As such, developing the ability to write an essay or solve a complicated equation for novices necessarily looks different to the way experts operate.

A popular way to overcome this for teachers is the worked example. This is where a % of the final product has been completed already, allowing students to appreciate the many constituent parts without being overwhelmed by generating them for themselves. An element of the final product may be left incomplete for students to do, with teachers safe in the knowledge that their working memory is not overloaded by the relatively meagre challenge.

Needham goes a step further and explains that “The most effective use of worked examples is to present a worked example and then immediately follow this example by asking the learner to solve a similar problem” (Needham, 2022).

If teaching students how to write an appositive sentence structure for example, the teacher may write an example as well as talking pupils through its constituent parts. Following this, they may present a semi-finished sentence, perhaps one missing the all important middle clause, and ask students to write an appropriate answer to fill it.

Over time, Needham also points out that “a curriculum that systematically and consistently uses worked examples should help students build a rich schema of ‘possible variations’, moving them quicker and more efficiently along the continuum from novice to expert than if they had just completed lots of writing tasks.” (Needham, 2022).

Let’s consider the pros and cons of the sage and guide respectively in terms of implementing higher order quizzing or worked examples:

Based on these considerations, the sage is again better placed to ensure skills or processes central to a subject’s discipline are encoded. Over time, these skills can be practiced and variations on the approach studied to ensure students move from novice to expert in an efficient manner.

Do we ever need to be the guide?

As explored above, if a curriculum places value on developing knowledge and foundational skills in service of higher-order processes or critical thinking then the sage on the stage is a vital component of achieving this goal efficiently and effectively. The MYP is one such curriculum and refers to the need for some ‘front-loading’ to happen so that inquiry can take place within their literature (although it is a shame that is only mentioned as early as p66 of the Principles into Practice).

Should a school or district decide that the sole aim of schooling is academic achievement and/or success on examinations then perhaps the guide can largely be dispensed with except at the very end of an instructional sequence.

However, the MYP is vocal in its belief of developing not only academics but also ensuring that students explore learning in a way that fosters collaboration, authenticity and reflection of one’s personal identity, amongst other commendable goals.

There is an opportunity for students to not only become proficient in each respective subject domain but also produce things that demonstrate individual flair, originality and thoughtfulness, following a period of reflection regarding what they already know, their experiences and/or personal passions.

This sequence can be modelled but not led by a sage given the diverse backgrounds of every classroom whether related to culture, interests or lived experience.

Undoubtedly, this is where the guide should come in.

Armed with the fact they have delivered or are delivering the knowledge and skills needed to operate in the domain, a teacher can pivot at points to the guide and allow students to take what has been learnt and head in a unique or self-elected direction.

If teaching students about the mystery genre with a view to writing a narrative opening, the transition between guide and sage might look like this:

This is of course a very simplified version of what can be an unpredictable and reactive process and this necessarily means opportunity cost is high for ensuring every last element of the explicit instruction sequence is ‘firmed’ or that students get as much time as they would possibly like for researching, drafting and feedback.

However, such a cost is incurred to ensure that some breadth of domain knowledge and skills are achieved as well as an acknowledgement of students’ creative or critical choices.

But do we NEED the guide?

The bottom line for most teachers is academic outcomes. Parental or professional pressure often revolves around children’s safety, happiness and success whilst at school. Unfortunately, the abiding and most transparent method of measuring one student’s success is the letters and/or numbers handed out at the end of Year 11 and 13.

Therefore, there may be a temptation to conclude that rigour is most reliably derived from direct or explicit instruction and that ceding any time to tasks that fall outside this model are ultimately superfluous.

This calls to mind David Perkins’ counter-argument that students of any age or discipline need to be able to “play the whole game” (Perkins, 2014). Endlessly studying how to play elements of a musical composition without ever hearing or attempting the full thing would be frustrating or at the very least unmotivating. Practicing free kicks and throw-in routines without ever engaging in a 7 v 7 or 11 v 11 at football training would also drain enthusiasm.

Even at the expense of further fact learning or skills practice, students deserve and benefit from seeing the wider application of their efforts and putting their own personal stamp on it.

Returning to Pooja Argawal’s paper, her findings include the idea that “building a foundation of knowledge via fact-based retrieval practice may be less potent than engaging in higher order retrieval practice” (Agarwal, 2019). This is still a vote in favour of the ‘sage’ approach but exemplifies the fact that if we want students to engage in complex, higher-order tasks in a subject, then they need the opportunity to take inflexible knowledge and skills and apply them in a range of contexts that develop more flexibility in their application. This necessarily mean the sage relinquishing their control and moving to the side to observe respective progress.

Interestingly, one of the seminal writers in the field of cognitive load theory, Paul Kirschner, has recently drawn attention to a paper in which he and colleagues found that “after initial acquisition, problem-solving leads to better long-term problem-solving performance than example study*. This holds true even for a relatively complex task and with limited instruction.” (Ruitenberg et al, 2025)

*example study here refers to the likes of a worked example.

If we want creative, authentic, significant and/or personalised outcomes for students following a unit of study, then we need to give them the opportunity to try, fail and ultimately succeed in creating these things.

The great mistake is attempting to do this at the outset or without sufficient instruction when students have limited base knowledge or appreciation of the constituent skills entailed.

The sage and guide binary is problematic as we need both in every unit and every year of study to deliver the IB’s MYP effectively. Consideration about when and how the sage or guide enter the fray are vital within a teacher’s planning or formative assessment.

Conclusions

The sage is far better equipped to establish and retain base knowledge and foundational skills among learners

The guide is valuable for ensuring students engage with a task through the lens of their own passions, interests, experience and/or knowledge

Interleaving these stances is vital for ensuring student motivation, learning and self-expression across a period of study.

References

Agarwal, Pooja. (2018). Retrieval Practice & Bloom's Taxonomy: Do Students Need Fact Knowledge Before Higher Order Learning?. Journal of Educational Psychology. 111. 189-209. 10.1037/edu0000282.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2015). Learning as a Generative Activity. Cambridge University Press.

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why Minimal Guidance during Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41, 75-86.

MYP: From principles into practice (IB, 2022) https://resources.finalsite.net/images/v1693234606/d11org/mwiovysnaivfp5wz5tz3/FromPrinciplesintoPractice.pdf

Needham, Tom (2022) Explicit English Teaching

Perkins, David (2014) Future Wise: Educating Our Children for a Changing World.

Sterre K. Ruitenburg, Kevin Ackermans, Paul A. Kirschner, Halszka Jarodzka, Gino Camp (2005) After initial acquisition, problem-solving leads to better long-term performance than example study, even for complex tasks

Sherrington, T. & Cavigloli, O. (2020). Walkthru's – Five step guides to instructional coaching. London: John Catt Educational Ltd. Topics.

Willingham, D. T. (2009). Why don't students like school?