What is the #1 Priority when Unit Planning?

Units are discontinued and replaced for a number of reasons. Backwards planning from A-Level / IBDP, a change in leadership or curriculum and a battered box of ancient, overused texts can all prompt a change.

The challenge facing Heads of Department or teachers tasked with creating the unit is what to prioritise as the unit’s core. At the beginning of my career, most units seemed to be divided by ‘Reading’ or ‘Writing’. Broadly speaking, ‘Reading’ would be a study of a novel, play or poetry anthology, whilst ‘Writing’ was either a narrative or rhetorical focus. Therefore, if a ‘Reading’ unit needed to be replaced, it would need a like for like replacement. Holes might be superseded by Chinese Cinderella. Blood Brothers might be replaced by DNA.

Leaving aside the questionable choices of text, is this approach the best way to go about refreshing the curriculum and what does it suggest about how the curriculum is assembled more broadly?

I’ve written previously about the competing demands for what to cover in English here. In less than 20 minutes, I had listed as many considerations that teachers may need to balance in terms of constructing the content of a unit of study. Forming some sort of hierarchy from these at times complimentary, at times contradictory elements is not for the faint hearted.

Below are what I believe to be the big players when it comes to considering a new unit and its place within the curriculum. As with anything, it is rooted in my current role’s requirements in terms of the IB framework but also my personal beliefs about what students need most to make meaning in English.

Provocative Topic

What I’m referring to here goes by a few names so let me try and list, at the risk of conflating, the many faces it could take: substantive concept, transdisciplinary concept, anchor concept, theme and/or global context.

For me, this is a topic that should provoke the students’ prior knowledge, experience and/or passion in some way. It is a topic or question that they can take home and discuss with their family. It is something they have standing knowledge about, having lived in the world, but can also build upon through the unit of study. It is an area where inquiry based teaching COULD conceivably happen.

This element of the course allows teachers to interleave the likes of poetry, non-fiction, newspaper articles, recent news events, short stories and more into the unit thanks to its unifying theme.

Examples I have seen, used or would like to use include but are not limited to: masculinity, monogamy, AI, sustainability, school life and our diet.

Some teachers, particularly those of an inquiry bent, like to formulate these into an ‘Essential Question’. Therefore, masculinity becomes: ‘What does it mean to be masculine in the 21st Century?’ and school life becomes ‘What should we learn at school and how should we learn it?’

Such questions then guide not only the focus and materials of the unit but also the students’ final assessment that should show some evidence of their personal engagement with the topic.

Disciplinary concepts

However, in addition to showing personal engagement, I would argue that a progressional model of learning relies on students also being able to demonstrate their engagement with disciplinary concepts.

Again, I have written about what I believe to be the big box concepts that every unit in English should cover (with only a little help from David Didau, Sam Gibbs and Zoe Helman!). These were: Structure, Grammar, Story, Argument and Context.

Despite this, each of them contains ‘smaller’ concepts that, when added to the student’s developing schema, help to strengthen the overall understanding of the big box concept therein. For example, Context can be broken down into the context of composition v.s. the context of interpretation. Taking these two things individually, the post-colonial context that Chinua Achebe was writing in was very different from the monarchical times that so affected Shakespeare’s work. For the context of interpretation, understanding the respective interests, concerns and beliefs of an audience is fundamental to graping rhetoric. Similarly, appreciating the different ways in which we ‘experience’ a novel, poetry and drama is key to understanding a writer’s choices.

Sequencing these aspects is a delicate process. What are the fundamental aspects that Y7s should learn about Story when entering high school? How do you stratify their understanding of Structure across 6 years of study? Didau, Gibbs and Helman have done a fantastic job of this and their writing is essential for beginning to grasp how a curriculum could be sequenced in such a way.

Nevertheless, there is an explicit requirement for ALL units to be constructed like this if a new unit is to be installed using the same approach. Should a teacher want to create a unit in this manner for the 2nd unit in Year 9, any hope of building on their past knowledge of Structure, Grammar, Story, Argument and Context is entirely contingent on what has come before. Should this approach not be installed throughout their English lessons up to this point, much of its content may fall on rocky ground.

Texts and Text Types

English has been described as a subject that is a mile wide and and an inch deep in terms of its knowledge and skills. Whilst I slightly contend the depth, there’s no doubt that this observation captures the vast expectations of any curriculum or teacher in the discipline.

Returning to the beginning of the article, discontinuing one text type i.e. a novel likely prompts discussions about which novel to replace it with. Contrary to this is the approach taken in many schools to teach through extracts or short texts rather than a 300 page work in its entirety. This has been met with disdain from some parents, some teachers and some policymakers alike who claim that it devalues the experience of literature that can only be gained through the immersive and complicated exploration of longer texts.

Putting that debate to one side, it does reveal yet another tension at the heart of English, that being the many forms of fiction and non-fiction that we are anxious for students to enjoy as well as understand by the time they leave school. Necessarily, they need to be au fait with the broad disciplines of novels / short stories, plays and poetry but therein lies a wealth of divergence in terms of genre, style and context. Similarly, one can arrange non-fiction texts into informative, descriptive and persuasive aims but this again obscures the hundreds of text types, conventions and techniques that writers use for a multitude of different purposes and audiences.

Backwards planning for A-Level or IBDP English reveals that students need not only a varied diet of texts but also a varied supply of vocabulary with which to break them down. This brings into focus the conversation around challenge, which Andrew McCallum has written about very succinctly here.

Hence, mapping when and why students encounter these many forms of fiction and non-fiction texts is vital for allowing a well-rounded appreciation of the 5 big box concepts previously mentioned.

Budgets and the Store Cupboard

I’ve worked in 5 schools now. Each of them has had very different capabilities when it came to purchasing power. My current one requires clear evidence for why new purchases need to be made and is monitored closely by a centralised auditor who isn’t known for pulling punches. As a result, changes to a set text have to be justified with a significant amount of teacher testimony as well as sturdy support for why its replacement is valid.

If other schools are similar, staples such as Holes, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas or Lord of the Flies are therefore stapled into the fabric of some curricula and only prised out once exhausted of their physical use or replaced once financially possible.

If teachers, curriculum leaders or Heads of Department identify a need through backwards planning or mapping out the aforementioned concepts and this comes into conflict with the texts currently in place, a move towards extracts and shorter texts available legally online may need to take place.

In the incredibly unlikely event that a long lost and unloved text from the store cupboard is remembered and subsequently maps well onto the new unit’s focus, financial constraints can of course be overcome. However, if this is not the case, in the long term, when funds eventually become available or saved towards, departments need a clear idea around which text will offer the disciplinary, style and perhaps thematic opportunities desired.

DEI and Decolonising the Curriculum

In recent years, educators have challenged the inclusion of some texts on the grounds that whilst conveying important disciplinary concepts and cultural capital, they also bring with them harmful stereotypes and problematic language.

Returning to the previous section, these may indeed include the long lost texts from the store cupboard that map amazingly onto the unit’s thematic and disciplinary needs but increase the Key Stage’s pale, stale and able-bodied male count +1.

If departments can effectively identify the theme, disciplinary needs and text type(s) required then conversations about which writing and therefore authors might be suitable. Undoubtedly, whatever the context a department operates in, there is inherent value in exposing students to a variety of perspectives across time and space.

But what of the arguments around offering the “the best which has been thought and said in the world”? This was an element of Michael Gove’s revamp of the National Curriculum in the UK, which was met with consternation by some and rapturous praise by others.

Clearly there is a need to offer appreciation of the canon and foundations on which literature resides but also the need to broaden students’ outlook and appreciation for new generations of world-class authors from diverging backgrounds.

The danger is selecting a text BECAUSE it is a canonical text or a text that offers a diverse view on life. Such an approach devalues both as they are shorn of any significance beyond their reputation or diversity respectively. Should they sit within a pre-chosen theme and disciplinary focus that justifies their selection, students will be able to not only draw upon their content for better appreciation of the subject but also see the inherent value that both types of texts have to offer in terms of their understanding.

Conclusions

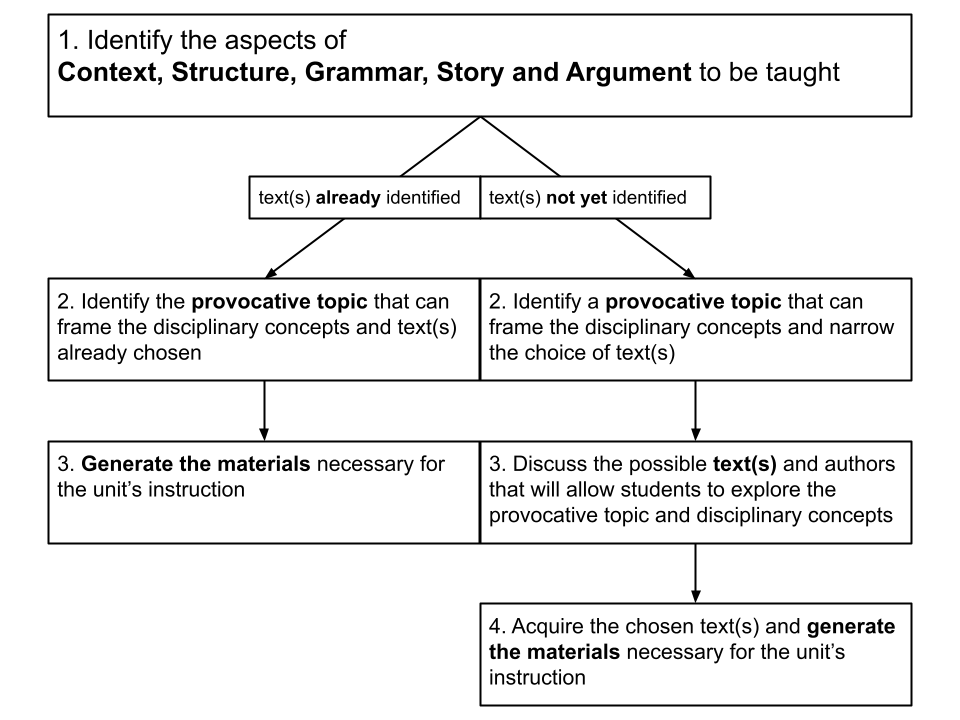

If constructing a progressional model for understanding, disciplinary concepts are surely the starting point for unit design. The reason for this being that whilst provocative topics may be essential for student engagement and agency, they are ultimately replaced by a new topic after 8 weeks that is not contingent on knowledge of the previous theme. Moving from mythology to role models may have some conceptual overlap but this is not necessary to achieve students’ interest.

On the other hand, beginning Y7 English with ideas such as context of composition, character, the 7 basic plots and word classes is inextricably linked to what will come next and therefore forms a intentional sequence of learning that strengthens their schemas with every new unit.

Once the respective aspects of Structure, Grammar, Story, Argument and Context are decided, types of text and their authors can then be discussed. Would students benefit from a canonical text at this point in the year or Key Stage or is this an opportunity for choosing a more contemporary text that will offer challenge AND a fresh perspective.

Alongside this consideration is the provocative topic that will be frame the unit. If teachers have a text or collection of texts in mind then a provocative topic can be generated retrospectively to fit these materials. Alternatively, a provocative topic can follow the disciplinary concepts therefore narrowing the field of texts a department might choose from. This is often achieved through a request to EduTwitter. Previous requests I have made include: Recommendations for poems that explore hope for the future? Can be natural world, living together etc. Variety of backgrounds appreciated!

@ing the likes of https://twitter.com/mrsmacteach33, https://twitter.com/FunkyPedagogy, https://twitter.com/Xris32 and https://twitter.com/GauravDubay3 amongst many others usually yields really helpful results.

Identifying such texts may still rely on the budget needed to purchase the necessary materials. This therefore requires a long term approach to planning and prioritising finances to ensure that the curriculum is being developed and balanced with what matters most in mind.

Here is a visual that hopefully makes the above more comprehensible: